Business owners in south-central Pennsylvania are seeing the same rapid-fire acquisition of local hospitals by UPMC that their counterparts a few counties to the north face.

But as veterans of several years of healthcare consolidation, they are less daunted by UPMC’s both-feet approach to the market.

“I would say at this point in time we’re cautiously optimistic” about the Pittsburgh-based healthcare giant’s entry into the south-central Pennsylvania market, said Diane Hess, executive director of the Central Penn Business Group on Health (CPBGH), based in Lancaster.

Then she quickly added, “I know that may seem strange to someone in Pittsburgh.”

It also may seem strange to the fledgling PA Employers Healthcare Alliance in Williamsport, which last week met to voice their concerns about UPMC’s purchase of four Susquehanna Health hospitals in their area.

At its most basic, the north-south difference in central Pennsylvania as seen by employer groups seems to come down to this: Business owners in and around Williamsport fear UPMC’s consolidation of previously independent hospitals will mean less competition, which will lead to higher premiums and restricted network access for their workers.

In Lancaster, Ms. Hess said, the consolidation ship has already docked and unloaded.

In the past five years, Lancaster General, that area’s largest hospital, has joined the Philadelphia-based University of Pennsylvania Health System and York Hospital is now WellSpan York Hospital, the flagship of the six-hospital WellSpan Health network that includes facilities in Gettysburg, Lebanon and Ephrata.

Reading Health System, the dominant provider in Berks County, has been rebranded as Tower Health and is purchasing five hospitals including those in Pottsville, Schuylkill County; Brandywine, Chester County; and Chestnut Hill in Philadelphia. And Holy Spirit Hospital in Camp Hill joined Geisinger Health System in 2014.

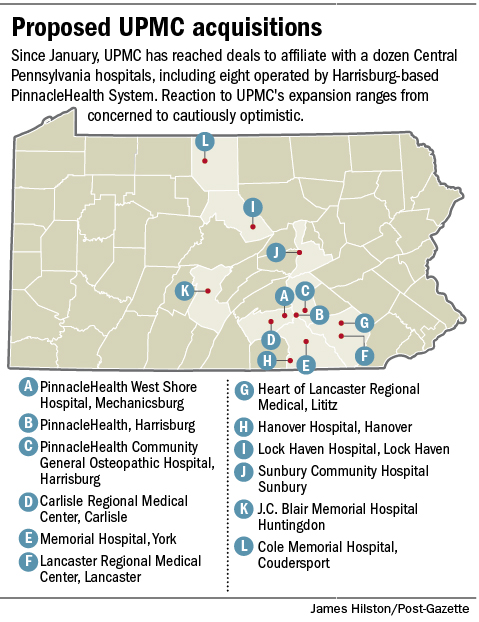

Given that recent history, small wonder that UPMC’s acquisition of PinnacleHealth’s seven hospitals this spring did not set off the same alarms their neighbors to the north are hearing.

“In one respect, it’s consolidation,” Ms. Hess allowed, “but you’re consolidating into a larger system that will compete with the larger systems that already exist in each of these communities.”

Paula Bussard, chief strategy officer for the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg, noted that perhaps fewer than 30 of the state’s 156 hospitals are still independent.

“The consolidation is there but it’s really the question ‘Why is there consolidation?’ that’s become more important.”

Particularly now that hospitals’ revenue has shifted to lower-paying outpatient care, independent community hospitals struggle financially to offer the full range of clinical services, she said.

“Being part of a system where there is clinical expertise can be very advantageous in improving the access to quality care.”

Ms. Bussard said she could not speculate on how consolidation might play out on the insurance side, where some employers fear their workers might face restricted in-network access to some hospitals.

“Employers need access to good quality care,” she said, and it is important that employers engage with both insurers and providers to address concerns about network access.

Consolidation in south-central Pennsylvania, meanwhile, is already a fact of life, Ms. Hess said, and the hope is that UPMC’s arrival will improve the health insurance picture.

Heather Stauffer, a reporter with the Lancaster newspaper LNP, was first to deliver the bad news last November: Central Pennsylvania has some of the highest insurance rates in the Commonwealth.

Commercial insurance terms typically remain confidential but the publicly available rates for the Affordable Care Act’s individual marketplace plans provide a peek into how insurers view Pennsylvania’s different regions.

For 2017, a 40-year-old nonsmoker in Pittsburgh could buy a medium range Silver Plan for a $232 monthly premium on the ACA marketplace. In Philadelphia, the cost would be $374.

The same plan for a Lancaster resident was $525 a month.

Reasons for the difference aren’t entirely clear, although a Pennsylvania Insurance Department spokeswoman explained that “plan prices are directly correlated with the cost of health care and companies’ claims experiences in each region.”

What is clear to employers are the bottom line numbers: Based on an internal survey last fall of CPBGH’s 145 member companies, “we know that our costs are higher than the national average,” said Ms. Hess. “We also know our deductibles tend to be higher so, particularly for smaller employers, that’s a concern.”

But can employers harness their collective purchasing power to do anything about it?

The better question may be whether they have the willingness and discipline to do it, suggested Jessica Brooks, CEO and executive director of the Pittsburgh Business Group on Health.

Mrs. Brooks, who was a guest speaker at the PA Employer Healthcare Alliance meeting last week in Williamsport, has presided over meetings locally where employers expressed concerns similar to those voiced last week in Williamsport. Once those meetings adjourn, though, she said members tend to go back to the office and work out their own deal.

“They still operate pretty independently, and that continues to be a challenge for me as leader of the coalition.”

Steve Twedt: stwedt@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1963.

Source: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Post a Comment