How Prescription Drug Rebates Work … But Don’t “Work” for YOU

By Vik Mangalmurti and Randy Main, Tonic Advisors

Have you ever gone to a restaurant with a friend and split the bill? You go, order a meal, talk, and when the check comes your friend says “let me put it on my card, and you can just give me half in cash. It will save me a trip to the ATM anyway.” It’s a normal enough interaction and if the total bill plus tip was $40, you fork over a $20 for your share. In some respects, this is the way standard copay and co-insurance models are intended to work at a doctor’s office or for a hospital stay. The bill comes, it’s for $1,000, your coinsurance is 20%, so you pay $200 and the insurance (your friend) covers the rest. This is how health insurance works…most of the time. It’s just that this isn’t the way it works in the pharmaceutical industry.

Most people probably think that the pharmaceutical industry should work something like the diagram below.

How We May Think the Rx Industry Works

This is the way we buy most goods and services. Someone makes them in bulk, sells them to a distributor and then the distributor sells them to retailers and the retailer sells them to us. We assume that the insurance that pays for our prescriptions works similarly. Most of us think that the difference is that we split the cost with the insurance company when we buy, or that we split the insurance company’s discounted rate. Actually, it often doesn’t work this way.

Instead, you go to the restaurant with your friend, order lunch, and your friend pulls out his credit card. You pay him $20 for your half. Your friend pays the $40 tab. What you don’t know is that your friend’s credit card has a deal with the restaurant. The restaurant sends 25% of the total tab back as a credit to your friend’s credit card. In the end, you pay $20 bucks for lunch and your friend paid $10. That’s a lot closer to the way it actually works in the pharmaceutical industry.

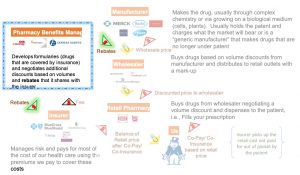

How the Rx Industry Really Works

In the middle of these transactions sits a Pharmacy Benefits Manager (PBM). The PBM helps insurance companies choose formularies (the lists of drugs the insurer will pay for) based on multiple factors. Some of these factors are clinical (Drug A is better than Drug B at treating a disease). Some of these factors are based on very standard cost concerns (Drug A and B are equally effective, but one costs less than the other). And some are based on undisclosed discounts and rebates, e.g., if the PBM gets to a volume of X on Drug A, the PBM will get 25% of the costs back as a rebate, which can be shared with the insurer.

The Problem

Above board discounts and rebates would not cause problems. Let’s say your friend had a coupon for $10 off when you bought two entrees. The price of the lunch would go from $40 to $30, and you would each pay $15. With the undisclosed rebate, however, you don’t get the benefit of the discount or rebate. All of the benefit goes to your friend (Your friend pays $10, you pay $20).

In most cases when you have insurance, you have an agreement to cover part of the costs, e.g., copay or coinsurance. The insurer covers the rest. Because you really don’t know what the net cost is to the insurer, you may be actually covering more than the amount you agreed on. When there is a copay and the cost of the drug is low, you may be paying more than the actual cost of the drug to the insurer in the first place.

In an extreme example, you could pay a $10 copay on a drug that “costs” $15 but where the insurer gets a rebate of $7 (making the actual net cost only $8). You are out $10, the pharmacist gets that $10 you paid plus an extra $5 from the insurer (total $15), but the insurer gets back $7 thus profiting $2.

Developments

The Trump administration seeks to limit use of such rebate agreements. The impetus is that current agreements often do not result in sound prescribing practices or fair market tactics and competition. Such agreements can induce insurers to put more costly drugs on formulary. After rebates and copays, the cost of some brand name drugs –to the insurer— can be lower than generic alternatives. The patient on the other hand may end up paying more.

The equivalent is your friend recommending going to the restaurant where his credit card gives him or her the rebate, even if the food is worse and more expensive. After the rebate, it is almost free for your friend. You, however, are stuck with a big tab, bad food, and an even worse taste in your mouth.

There are likely to be many on the left (or in the party that begins with D) who don’t care for this change in policy because it comes from an administration that begins with “T”. We do not suggest that the changes proposed are perfect. More specific implementation plans would be helpful for analysis. We only urge critical analysis of the proposal on the merits of the proposal itself and its goals rather than its political source. The proposal is a solid start towards increasing transparency in drug pricing.

Please give us feedback

We know we have oversimplified. There are nuances and complexities we did not delve into; but we did so because we didn’t want to lose sight of our main purpose. We believe we captured the gist of the dynamics of product (medicine), money, and information flow in the pharmaceutical industry. As specifics become clear about the proposals, we will update. As points are made in response to this article, we will respond so that we can keep the discussion going. We look forward to a virtual dialog with the readership.

Rory

How much money are we talking about in total nationwide? Is this a big source of escalating healthcare prices or pretty minimal?

Vik Mangalmurti

Hi Rory, thanks for the question. I have seen estimates published in Health Affairs based on data by Altarum that the rebates in 2016 were around $89 Billion. Given overall medical inflation I would guess that they are currently between $95-$100 Billion today. this is about 3% of the total healthcare cost of the U.S. Rebates are not a cost per se–they don’t directly add to overall expenditures. They are just a classification of how some money changes hands. The issue with rebates is that they are big enough to create a powerful incentive to behave in one way as opposed to another. If that incentive generates useful results (for example drives higher quality medical outcomes), then few people would be concerned. The fear is that they may at times generate unfavorable outcomes or needlessly higher costs. Understanding how much this contributes to the cost of healthcare depends on a different calculation. It would be interesting to see a study that demonstrated to total overall inefficiency in drug prescribing and filling based on A) use of brand name drugs when suitable generics were available, + B) use of less effective or generally more costly drugs in place of more effective or less costly drugs and C) an analysis of what portion of A + B are driven by rebating incentives as opposed to poor training or knowledge of available alternatives.

Jeff

Isn’t the HHS rebate proposal specific to Medicare and Medicaid only? I saw some news regarding a senate bill that would expand this to Commercial markets as well. Should all markets be treated equal?

Vik Mangalmurti

Hi Jeff, yes absent some congressional legislation, the proposal is limited to federal programs. It is worth noting though that the rebates are a bigger portion of the total cost in Medicare Part D (Prescription drug program) and Medicaid than in commercial. It is also worth noting that policies that the federal government puts in place have a tendency to trickle down. Certainly congress can mandate greater transparency should it choose to act.

Dan Henderson

Gents: as I mentioned on LinkedIn, the specter of the consumer paying more in a copayment or coinsurance than the actual cost of the drug to the insurer is indeed troubling. A 3/13/18 JAMA article illustrates your contention quite well and provides a highly detailed analysis of the frequency and magnitude of the overpayments. Perhaps later on in your series you could delve into the impact of what a monopsony like Medicare is having on overall cost and drug supplies. Looking forward to reading the next article in your series!

Vik Mangalmurti

Thanks Dan. The effect of leveraging the massive buying power from federal programs (Medicare, Medicaid, VA, IHS etc.) on drug prices is an interesting topic and one that we will look into as we see more discussion of changing health coverage options (universal health care, Medicare for all, Medicare Advantage for all, expanded Medicaid etc.) going in to the next election cycle. For those interested in the article Dan referenced, here is a link to the abstract.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2674655